November 11, 2024

Radical empathy: When caring for green spaces means caring about people

By Karina Sinclair

By Karina SinclairAaron Harpell joined the landscape profession in a conventional way, but his green industry experience sparked another long-time desire to make a positive impact on the lives of people in this community.

After graduating from the Landscape Technician program at Humber College in the mid-2000s, Harpell worked for companies providing residential design, build and maintenance services for affluent areas in Toronto, Ont., such as Forest Hill, Hogg’s Hollow and the Bridal Path. “Those were great. I learned a lot. And, as I progressed, I became interested in doing a bit more,” Harpell said. “I've always had a passion for environmentalism and social justice, and I was trying to find a way to marry my love of the green and the landscape industry with that.”

Although Harpell loved working within the beauty of a well-maintained garden, he felt a calling to make a difference. “I wanted to have a measurable and meaningful impact on people's lives,” Harpell said. “I didn’t want to make rich people's houses look beautiful; I wanted to make everyone's city healthier.”

So he moved to Evergreen, a Toronto non-profit dedicated to building public green spaces in urban environments. Over the next decade, Harpell oversaw the gardening staff at the Evergreen Brickworks campus in the Don Valley, helped launch Evergreen Garden Market and became involved in emergency management during flood events.

Aaron Harpell.

Aaron Harpell.

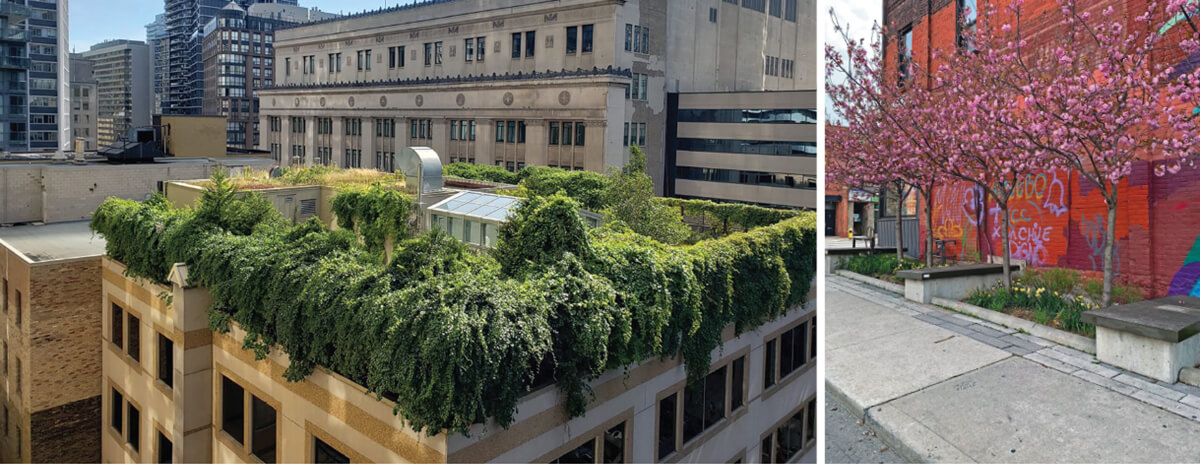

A space where everyone can grow

Harpell is now the business manager at Parkdale Green Thumb, a social enterprise landscaping program owned by Toronto non-profit Working For Change. “A social enterprise is a business run by a non-profit organization. It’s generally understood to be profitable and needs to contribute back to the organization,” Harpell explained. “Parkdale Green Thumb is a different kind of social enterprise. It's called a workplace integration social enterprise, or WISE for short. We hire individuals who, for various reasons, have trouble entering the workforce. They might be new to the Canadian workforce, or there may be other barriers based on their lived experiences. There are lots of workplace integration social enterprises across the city, but we're one of the few landscape-based ones in Ontario.”Parkdale Green Thumb works mainly with institutional clients, and offers seasonal planters, groundskeeping, garden maintenance and indoor plant care. “We also do green roof maintenance, but we’ve shied away from snow removal because it’s too physically taxing for our staff,” Harpell said, adding that his crews also perform street sweeping and litter pickup. Those aren’t preferred projects but do offer year-round work, which can be critical for providing stability. “Ninety-five per cent of my staff are on some sort of public assistance and they’re living on the margins. When we have work, we try to get them as much as we can. If I had more indoor, year-round clients, that would be amazing, but it’s not what we have right now.”

People before profits

Unlike a conventional for-profit business, Harpell says a WISE serves both the client and the employees in deep and measurable ways by offering employment environments that support recovery and overall wellness, remove social isolation, reduce financial stress and address poverty.“There’s mindfulness in every decision we make. Like any company, we think about what's profitable and makes sense. But we also ask, ‘Who are we serving?’” Harpell said, adding that sometimes that means operating in a less efficient manner or sacrificing some profitability if it means putting their staff’s needs first.

“Sometimes I have to turn down projects because the parameters are beyond my staff’s capabilities,” Harpell said. “That makes it tough because I want to give them as many work hours as possible, but I also need to ensure they'll be successful. If we take on a project that’s too much, it could be detrimental to their lives. So, it's complex in that way.”

Managing a WISE comes with many challenges, such as scheduling. “Sometimes we over-schedule, knowing some staff may not show up,” Harpell said, referring to his schedule as a ‘living document.’ “We make sure to have enough people to get the job done, even if a few can't make it. As staff get more comfortable in the program and more confident in themselves, attendance improves. But it’s a challenge and every day we have to figure out what's going to work.”

At Parkdale Green Thumb, Harpell leads a team of roughly 30-35 part-time and full-time crew members over the course of the year. It’s not unusual for some staff to become inactive or disappear for periods of time, but he maintains an open-door policy. His employees know they can rejoin whenever they want. “We bring a radical empathy to our work,” Harpell said. “We want people in crisis to know they can return when they’re ready.”

Finding the yes

Harpell acknowledges that a conventional employer might find many reasons to say no to hiring employees from disadvantaged backgrounds, but encourages them to “find the yes.”Adamant the extra effort is worth it, Harpell shared how he’s seen employees transition from living in a homeless shelter to securing their own apartment, or existing on one meal a day to being able to afford better nutrition. Giving an opportunity to gain financial stability helps in so many ways.

“Providing wages has a direct impact on their quality of life. If somebody can and does develop a career, they can hopefully move beyond us to a conventional employer — and in doing so, off of public assistance. So that's important. That's a beneficial outcome for everybody,” Harpell said. “Another thing is providing these individuals with community. A lot of our staff has felt or been isolated from a supportive community for significant portions of their life. Being able to begin to trust people again — I mean, that's powerful. That's incredible. How do you put a price on that?”

The business of building people up

“I had a staff member who, when they first joined us, was selectively mute,” Harpell said. Selective mutism is an anxiety disorder where a person is unable to speak in certain situations. At first, the employee would write things down on paper to communicate. “Three years later, this individual has gone on to lead walking tours through some of our public-facing projects. This employee has also hosted a tour of a series of pollinator gardens that we've done. Amazing stuff. So that is absolutely part of why you do this. Building these people up, helping them feel a sense of belonging and security. And sometimes they’re feeling that in a meaningful way for the first time in their lives.”Any business can make space for employees from disadvantaged backgrounds. Harpell says hiring managers just need to be comfortable with being uncomfortable. “To hire somebody who has a challenging, marginalized background, you need to take time to build that relationship and that may not feel so easy in April, May or June because we're go-go-go and want to get projects done,” Harpell said. “Bring patience to it. Be aware that there will be setbacks and hiccups and misunderstandings because these people come with lived experience that is dramatically different.”

Harpell hopes other employers will become more open-minded with how they recruit new staff. He’d also encourage conventional managers to reexamine their operations to eliminate obstacles. For instance, be flexible with schedules and stop requiring doctor’s notes for sick day requests. “Ask yourself, ‘why do I need this? What are the barriers that I'm unknowingly erecting that would keep marginalized people out?’” Harpell said.

Harpell also suggests reaching out to local organizations who help facilitate workplace integrations to learn how to be a more supportive manager. “I come from a landscaping background. I didn't come from a social worker space. I'm lucky the organization that I joined has given me the space to learn what I've had to learn and given me opportunities to speak with experts,” Harpell said. “And honestly, one of the places where I've learned the best has been from my staff. They are the experts on what they deal with and what they need. It's tough because they are dealing with more challenges by eight a.m. than a lot of people deal with their entire week.”

A force for change

Some days, Harpell wishes his social enterprise wasn’t needed. “I would love to be able to just hang it up, walk away and say I'm not needed anymore. That would be absolutely phenomenal,” Harpell said. “And then I could just do the gardening that I love to do. That, unfortunately, is not going to happen anytime soon.”So he’ll continue to open doors and knock down barriers for his staff for as long as he’s able. “Ultimately, I do want to be a force for positive change in the world around me. And I think most people do,” Harpell said. “This is the expression that I've chosen for that change so far in my life.”

An active Landscape Ontario member since 2006, Harpell also volunteers with the association’s Diversity, Inclusion and Belonging committee. “I very much value the work that we do there, and the ways in which we try to move our collective industry along to become the best version of itself. To make sure that this is a place that anybody, regardless of background or lived experience, can find a place if they're interested, not just to exist, but thrive,” Harpell said. “And so I take that role very seriously. It’s close to my heart.”

Harpell is happy to share his insights with fellow Landscape Ontario members and encourages them to expand their perception of the ideal candidate. “If you make space in your organization for somebody who's got a unique set of challenges, you will find that you have a richer organization because of it,” Harpell said. “You will have a diversity of knowledge and experience that you weren't expecting. You will be surprised at how strong you can be and how much more rewarding work can be.”