March 1, 2014

Unit pricing, good intentions and poor results

BY MARK BRADLEYI believe most contractors understand that unit pricing should be avoided wherever possible. It’s not consistently profitable. It lowers the bar in our industry. Occasionally, we’re all forced into a scenario where unit pricing is required such as a tender or working for an architect, but it should be avoided unless absolutely necessary.

But, although many contractors have grasped this concept, unit pricing is still very much alive and well. For reasons that might include speed (needed this estimate yesterday!), lack of a proven alternative, or simply avoiding change, a large percentage of landscape contractors stick to pricing work by the size of the area or the cost of the materials, instead of using a pricing system based on the true costs of completing the job.

Why change?

If you’re happy where you are, and your profitability is good, perhaps you don’t need to change. But if you’re struggling with people, profits, growing into larger jobs, or selling work, let’s look at a few real-world examples of why you must change.

One of the oldest pricing methods in the book is the square foot method. You might use this method to quote lawn maintenance, snow and ice control work, or installing decks or pavers. But let’s take a look at some real-world examples of how this method falls apart.

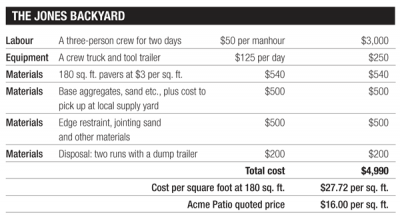

Job A: The Jones Back Patio. Mrs. Jones would like a patio off their back door in a backyard with poor access. The total size of the patio is 180 sq. ft. The Joneses are very budget conscious and want a budget-friendly solution. The fictional Acme Patio Co. has done Brussels Block patios dozens of times before, and prices the work by their old standard: $16 per sq. ft. installed x 180 sq. ft . = $2,880 total price.

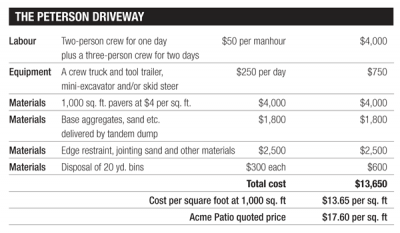

Job B: The Peterson Driveway. As Acme Patio commences work at the Jones house, the Petersons approach them about their driveway. They’d like to rip out their existing asphalt and install a new 1,000 sq. ft. driveway from garage to street. They request a quote, and the Acme Patio estimator looks at the job with the following adjustments:

- The bigger square footage and easier access will result in improved efficiency. He estimates improving 20 per cent for speed and productivity

- The deeper base will increase excavation and base installation. He increases the costs by 20 per cent.

- The Petersons want a slightly more expensive paver called Avante. It’s 25 per cent more expensive than the Brussels Block, so that he ‘estimates’ he needs another 10 per cent added to the job’s price.

- With a final price of $17.60 per sq. ft., he figures the job will cost $17,600.

- Mobilization/de-mobilization of the job and the equipment, setting up the site, delivering materials

- Excavation; true, it’s somewhat based on size, but access and equipment availability swing excavation time from a few hours to a few days.

- Base installation; only materials here are determined by square footage. Here, you could dump a tandem of base right into the excavated drive, whereas the back patio’s gravel gets dumped in the drive, then carried to the back one wheelbarrow at a time.

- Avante pavers come in pre-assembled clustered stones to achieve their random pattern. Each Brussels Block is individual. Installation time of the Avante paver takes half the time or less to achieve a random pattern.

- The Jones patio has a curve on one side requiring careful measurements and cuts to be made. The Peterson drive is straight, with few cuts.

|

|

These two jobs aren’t just a little bit different per square foot, they are miles apart. A random 20 per cent “difficulty” factor isn’t going to save either job. The per square foot price is more than double the difference. Even if Acme Patio’s estimator got a little more aggressive with the driveway pricing and even if he added a 25 per cent increase to the back patio’s price for its difficult access, Acme is still destined to lose money on the one hand and lose a job on the other.

If Acme Patio’s bid runs up against a competitor who looks at each job’s labour, equipment, materials and subcontracting costs to calculate its price, Acme Patio is in a world of trouble. They’re going to win every one of the Jones backyard jobs, but they’re not making a penny. And, vice versa, they’re going to lose a lot of profitable driveways and larger jobs to their smarter, more accurate competitor.

And the most ironic part about it? Acme’s wondering how their competitor bid that driveway so cheaply, and yet drives around in new trucks and trailers.

There are a few simple steps to help ensure all your jobs have a realistic chance to make a healthy profit.

Use equipment, material selections, and material delivery/disposal methods that reduce labour and time to complete

Price jobs using labour, equipment, material and subcontracting costs and know your overhead markups

Train your crews on the most efficient methods to complete the work, concentrating especially on layout, staging and order of operations

Keep score. Motivate your staff with expected hours on every job, then track their progress.

The good news? There’s still a whole bunch of Acme Patios out there in our industry. Grab 2014 by the horns and make every job a profitable job.

Mark Bradley is president of TBG Landscape and the Landscape Management Network (LMN), both based in Ontario.