August 4, 2021

Adam Papple, from Perfectview Decks and Landscaping, works on deck stairs at a job site in Oakville, Ont.

Lessons from the lumber price spike

BY TANIYA SPOLIA

Nestled at home, in the midst of a pandemic, homeowners took the last year-and-a-half to invest in the space they could spend time in — their property. However, as demand for raw materials surged and production dipped, getting any work done was met with a hurdle: skyrocketing lumber prices.

“I guess when [COVID-19] first happened, March or April of last year, and things got shut down — the expectation at the time was that construction would suffer,” says Mike Phillips, the executive director of the Ontario Structural Woods Association. “And so, primary manufacturers reduced operations, and whatnot, but then the reality was after a short period construction resumed and this whole sort of mania of consumers building decks, fences and home renovation projects just took off.”

Demand for lumber went through the roof as people scrambled to make their work-from-home experience fit their new pandemic lifestyles. In tandem, supply remained tight as producers faced a limited ability to ramp-up production in light of at-work capacities and inventory shortages.

“It’s made life complicated [for our members], you know, having to tell your customers ‘it’s going to take me a bit longer than anticipated to get your products’ and things like that,” says Phillips.

For customers, these supply issues have led to increased wait times, being unable to obtain certain products and of course, increased prices.

Rajat Dham, a homeowner in Aurora, Ont., is tearing down an infilled bungalow and building a brand new home from the ground-up.

“There’s two ways [increased prices] have impacted us,” explains Dham. “One is pricing itself — we were over budget before we even started the project. The second way it’s hurting us is that even though lumber prices have come down, it’s still on a very high note for consumers … since the demand is still so high, consumers are yet to see a direct benefit from the decrease.”

With increased prices consuming the majority of his budget at the beginning of the project, it will leave less money for his landscaping, decks and other home-oriented expenses. Till now, Dham has been eating the majority of the increased costs and he doesn’t blame his contractor for it.

“The price differential is so humongous that it will eat into all his margins,” says Dham. ”It’s one of those things where you have to be a partner to your builder and understand that they’re actually paying much more for their lumber than they were before.”

While some contractors have opted to shift price increases onto the consumer, other companies were forced to eat the costs themselves.

Alex Guiry, a design consultant and project manager at Oakville, Ont. based Perfectview Decks and Landscaping, says jobs booked and priced before lumber prices skyrocketed have impacted the company’s bottom line.

“So you get your jobs booked at old prices, which are a sliver of what they are now,” she explains. “By the time the projects rolled around, the price increases were huge. By mid-summer (2020), it felt like you were just bleeding money.”

As a boutique contractor, Guiry also points to the fact that smaller companies don’t have the option to stockpile inventory like bigger organizations. This made sourcing material, especially last summer, nearly impossible.

“It was literally like the Wild West,” she laughs.

As COVID-19 continued, they were able to reduce the number of projects they were taking on — focusing on one customer at a time to deliver above-expectation results and manage the lumber crisis.

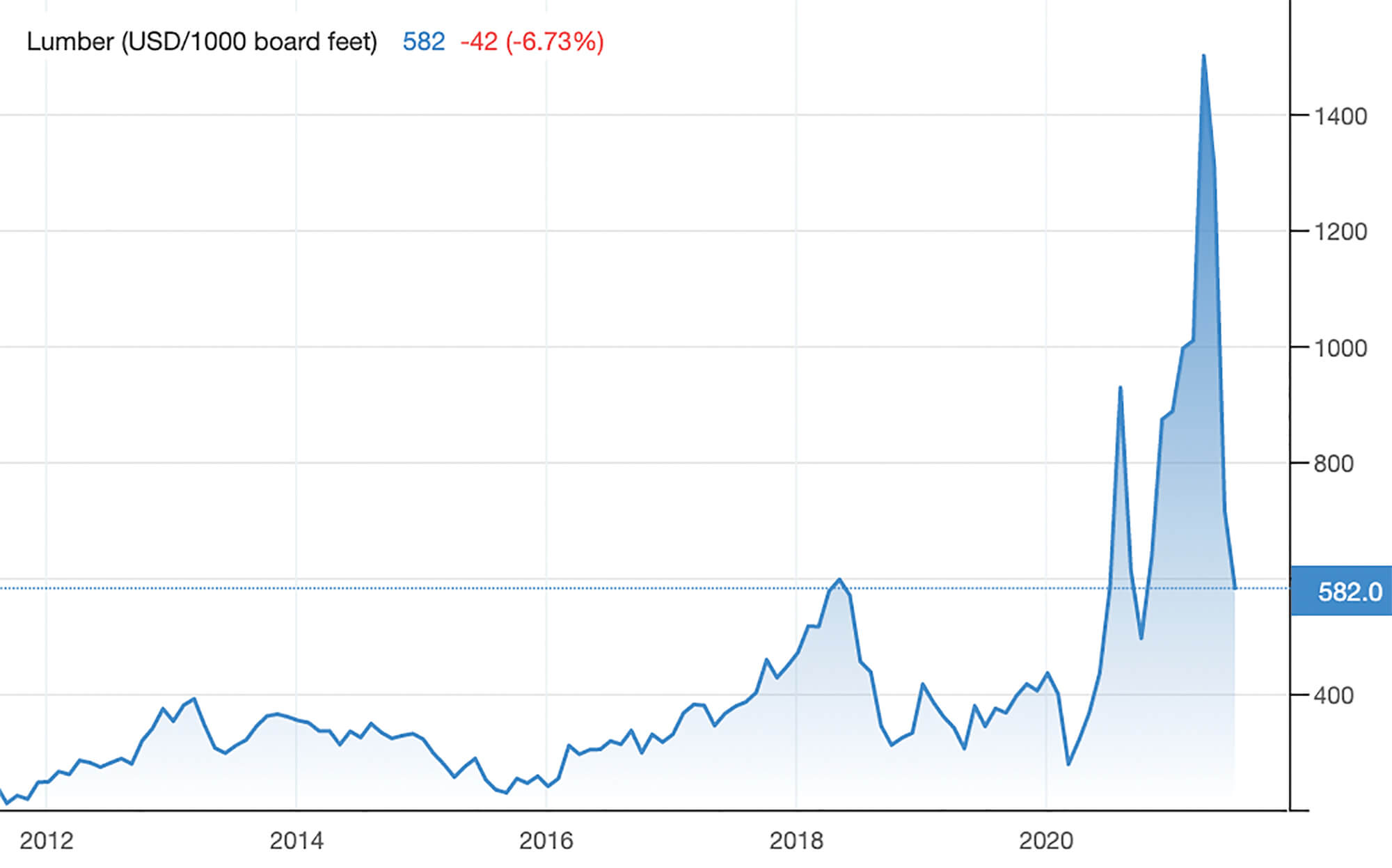

In the summer of 2021 lumber prices started dropping. However, the dip could be as temporary as the surge, begging the question — what can companies do to mitigate price fluctuation risks going forward?

Lumber prices peaked on May 7, 2021 at $1,686 USD per thousand board feet.

Lumber prices peaked on May 7, 2021 at $1,686 USD per thousand board feet.

“It’s hard to control for these things, but it’s important to know these giant swings can happen,” says Guiry. “We’ve talked about not having fixed prices — like at a restaurant, where meat might depend on market price — but then guaranteeing that it’ll only be within a certain margin … so we’ve talked about it, but we’re also on the fence, like ‘Can we even do that, would consumers be okay with it?’”

At the same time, she recognizes the risk is also part of doing business.

According to Dham, however, this innate risk can perhaps be mitigated by diversifying material portfolios — especially exploring more sustainable options that are now pricing at par to traditional materials.

“So, my frustration is — especially from a trades perspective — is that while a lot of things are beyond our control — the supply chain or the stock market, for example — there are also things in our control,” explains Dham. “The standard, or status quo, in control is in innovation and the modernization of technologies.”

With an increased reliance on a single commodity or product, like lumber, surges as such can have a drastic impact on everyone involved. Having other alternatives available for consumers can provide options that would perhaps soften the blow when prices for commodities like lumber skyrocket.

“The [price] gap between more eco-friendly, modern products and traditional materials have shrunk quite a bit,” says Dham. “I think it’s an interesting time for us to investigate why we aren’t exploring new materials and why it’s harder to get permits to use them. Right now, there are very few people and towns who have been proactively spending time and money to learn about and approve alternative products.

“I think this is a great opportunity and responsibility the [lumber] industry can look into, and bring municipalities in as well. The demand for lumber — new houses, renovations and whatever else — is only going to increase.”

Looking forward, the price of lumber, or any commodity, is unpredictable. Recognizing this, however, opens the opportunity to explore what companies can do to manage fluctuating costs, decrease single-product reliance and explore new alternatives and product innovations.