June 30, 2016

Blacklegged ticks in Ontario: A primer

By Curtis Russell, Public Health Ontario

In the last few years, Ontario has seen an increase in the number and distribution of blacklegged ticks, Ixodes scapularis. This species of tick, sometimes called the deer tick, is the primary vector of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease in eastern North America. Over the last decade, Ontario has also seen an increase in the number of human cases of Lyme disease; making it the most common vector-borne disease reported in Ontario. This can be attributed to the increase in blacklegged ticks, but also to the increased awareness of the disease, both by the public and health care professionals.

In the last few years, Ontario has seen an increase in the number and distribution of blacklegged ticks, Ixodes scapularis. This species of tick, sometimes called the deer tick, is the primary vector of the bacterium Borrelia burgdorferi, which causes Lyme disease in eastern North America. Over the last decade, Ontario has also seen an increase in the number of human cases of Lyme disease; making it the most common vector-borne disease reported in Ontario. This can be attributed to the increase in blacklegged ticks, but also to the increased awareness of the disease, both by the public and health care professionals.

Blacklegged tick life cycle, feeding habits and habitat

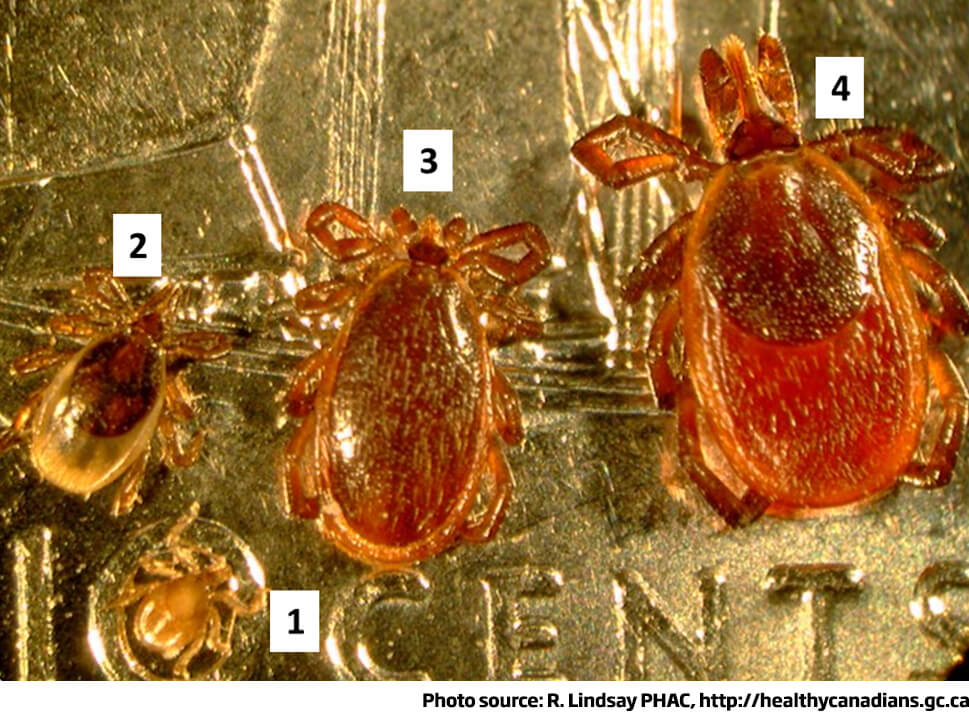

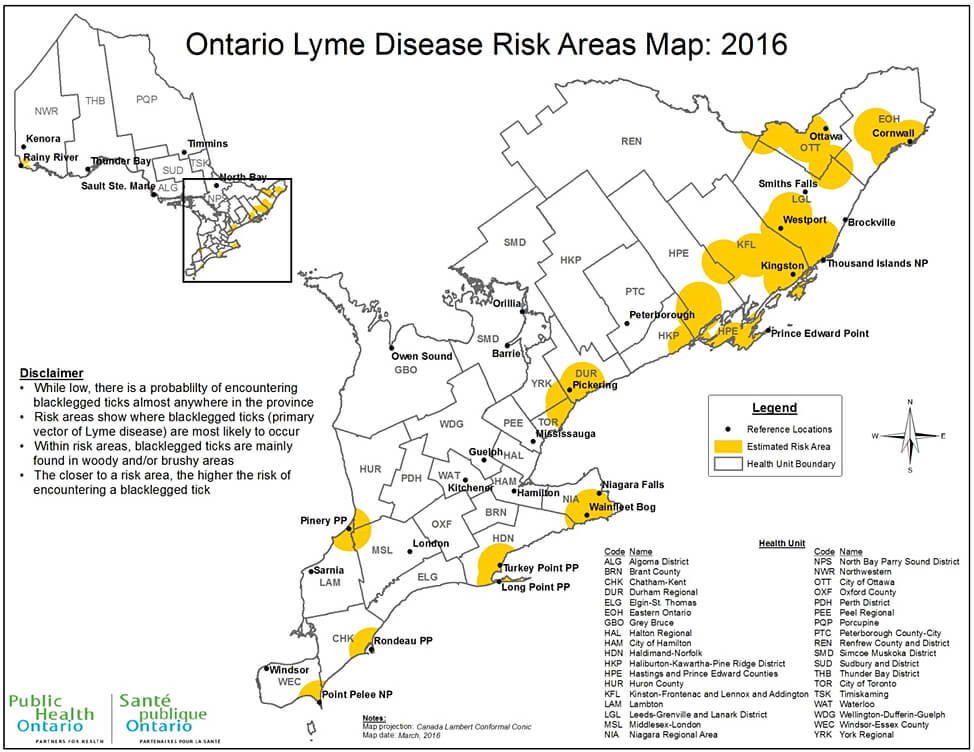

After the blacklegged tick hatches, it goes through three life stages: the larva, nymph and adult (Figure 1). All of these stages will feed on a variety of hosts. The immature stages (larva and nymph) usually feed on small mammals, such as the white-footed mouse, while adult ticks are typically found on deer. Since the immature stages also feed on migratory birds, there is a low possibility of finding a blacklegged tick almost anywhere in the province. Blacklegged ticks are predominantly found in, and along the edges of, deciduous or mixed deciduous areas. These types of forests typically have leaf litter on the ground, which provides a moist area for the ticks to go into when it gets too hot for them, as they are prone to drying out. In Ontario, these areas are mainly along the north shores of Lake Ontario, Lake Erie, the St. Lawrence River and the Rainy River area of northwestern Ontario (Figure 2.) While these are the main locations for coming into contact with a blacklegged tick, it’s important to that note that within these areas the blacklegged ticks are found in brushy/wooded areas. For properties in these areas, it’s possible to reduce a potential tick exposure through some level of landscaping, such as placing mulch between the property and adjacent brushy/wooded area (www.cdc.gov/lyme/prev/in_the_yard.html).Blacklegged ticks and Lyme disease

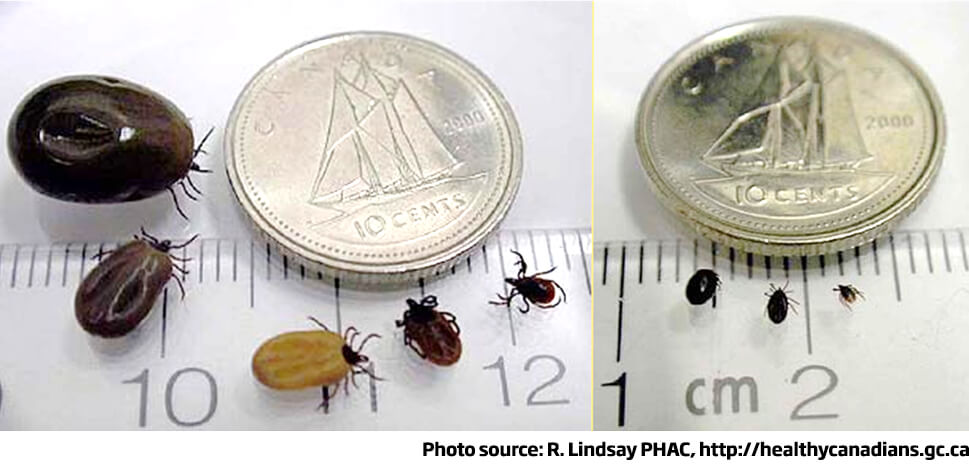

Not all blacklegged ticks carry the bacteria that cause Lyme disease. It is important to note that if a blacklegged tick is infective, it must feed for at least 24 hours before it is able to transmit the bacterium. Adult blacklegged ticks are typically found in the spring and fall, while the nymphs occur in the summer months. Due to the nymph’s small size, it is more likely to go unnoticed and be able to feed for more than 24 hours. This makes the summer months the time of greatest risk for people to acquire Lyme disease in Ontario (Figure 3).

Figure 1: Blacklegged tick life stages located on a dime for size reference, larva (1), nymph (2), adult male (3), adult female (4).

Figure 2: A map showing Ontario’s Lyme disease risk areas for 2016. Additional information on Ontario’s risk areas can be found at: www.publichealthontario.ca/en/BrowseByTopic/InfectiousDiseases/Pages/IDLandingPages/Lyme-Disease.aspx

Figure 3: Adult and nymph pre- and post-feeding

The picture on the left shows an adult female blacklegged tick as it size increases during feeding, from right to left. The picture on the right show the size changes for a blacklegged nymph, from right to left.

What you can do?

For people to reduce their chances of becoming infected, it is important to reduce their exposure to blacklegged ticks. Here are some tips:- When in habitats where ticks may be found, it is best to wear light-coloured, long-sleeved clothing and use an insect repellent with DEET.

- Once you leave the habitat, check your body for ticks; you may need help from someone else to check hard-to-reach areas.

- When back at home, all clothing should be put in the dryer for at least an hour to kill any ticks that may have latched onto clothing.

Take a shower, or bath, so that any ticks on the skin may be spotted and removed or, if any ticks have not attached, they may be washed off.

If a tick is found attached, the only recommended way to remove the tick is to use tweezers, grab the tick as close to the skin as possible, and pull it straight out. All other methods of removal, such as burning the tick or covering it in petroleum jelly, are not recommended. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides information on how to properly remove a tick (www.cdc.gov/ticks/removing_a_tick.html).

If you find a tick on you, you can contact your local public health unit to see if they will accept and submit it for identification and testing. This is done to allow public health officials to track the spread of blacklegged ticks and the Lyme disease bacterium and not for the purpose of clinical diagnosis. If you are concerned about your health, please see your health care provider and let them know if you found a tick on your body, where you were and if the tick was on you for longer than 24 hours.

For additional resources on ticks and Lyme disease, please visit:

Public Health Ontario:www.publichealthontario.ca/en/BrowseByTopic/InfectiousDiseases/Pages/IDLandingPages/Lyme-Disease.aspx

Ministry of Health and Long-Term Care:

www.health.gov.on.ca/en/public/publications/disease/lyme.aspx

Government of Canada:

www.healthycanadians.gc.ca/diseases-conditions-maladies-affections/disease-maladie/lyme/index-eng.php

Local Public Health Units:

www.health.gov.on.ca/en/common/system/services/phu/locations.aspx